The Folger Shakespeare Library recently opened their newest exhibit Breaking News: Renaissance Journalism and the Birth of the Newspaper on September 25. The exhibit runs through January 31, 2009 and is free to the public. I recently had a delightful Q&A session with Jason Peacey, one of the exhibit’s curators and a Lecturer in History at University College London, and Amy Arden at the Folger here in DC.

Give us an idea what a visitor to the Folger’s latest exhibit should expect.

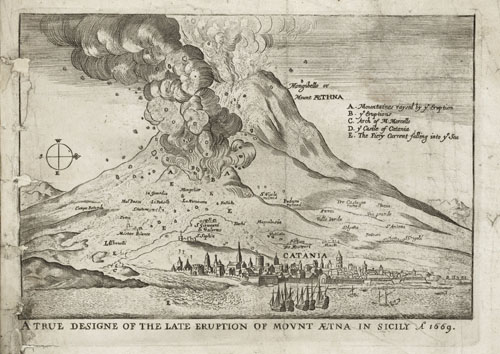

Breaking News follows the story of the newspaper from England to America. Visitors will see many things that they recognize, from the kinds of topics covered – politics, natural disasters, extreme religious sects, crime – to the actual format of newspapers from this period with headlines, columns, and serialized issues. One thing that may surprise people is how much of a role wartime reporting played in launching the newspaper; during the 1640s civil war raged in England between the supporters of the king (known as Royalists) and the supporters of Oliver Cromwell and Parliament (the Parliamentarians). Both sides produced their own accounts of the conflict and printed newspapers in an attempt to sway public opinion in their favor. It was a ripe time to be a journalist!

In your opinion, has political propaganda changed any since the advent of the printing press, based on the subject of this exhibit?

I would argue that in fundamental ways little has changed in terms of the techniques available to politicians for manipulating the press over the centuries. People may have become more adept and using such skills, but the basic skills have not changed. It was possible by 1700 not merely to produce overt and transparently official propaganda, but also to employ writers surreptitiously, to float stories in order to prepare public opinion for policy changes and policy initiatives, to engage in deliberate falsification and manipulation of stories, not least in order to blacken reputations. Politicians quickly realized that they needed to address a variety of audiences, and through a variety of styles. They could be serious, but they could also ‘tickle the public’ (an seventeenth century phrase which survived into the 20th century language of journalists, who apparently did not know its origins), and they could wage multimedia campaigns on certain issues at

certain moments.

How important is this exhibit, considering society’s increasing reliance on electronic media and non-traditional news sources, as opposed to print?

We hope to have shown that the news media has always been undergoing change, and that the current changes are only a continuation of this. Formats and styles changed rapidly over the years, but some of the key elements of modern newspapers emerged fairly quickly, and have remained common ever since. More importantly, they can still be found even on non-paper news media. Our other aim was to suggest that the key factors promoting and provoking change in the renaissance period (war, commerce, and struggles over political control) remain the most important ones today.

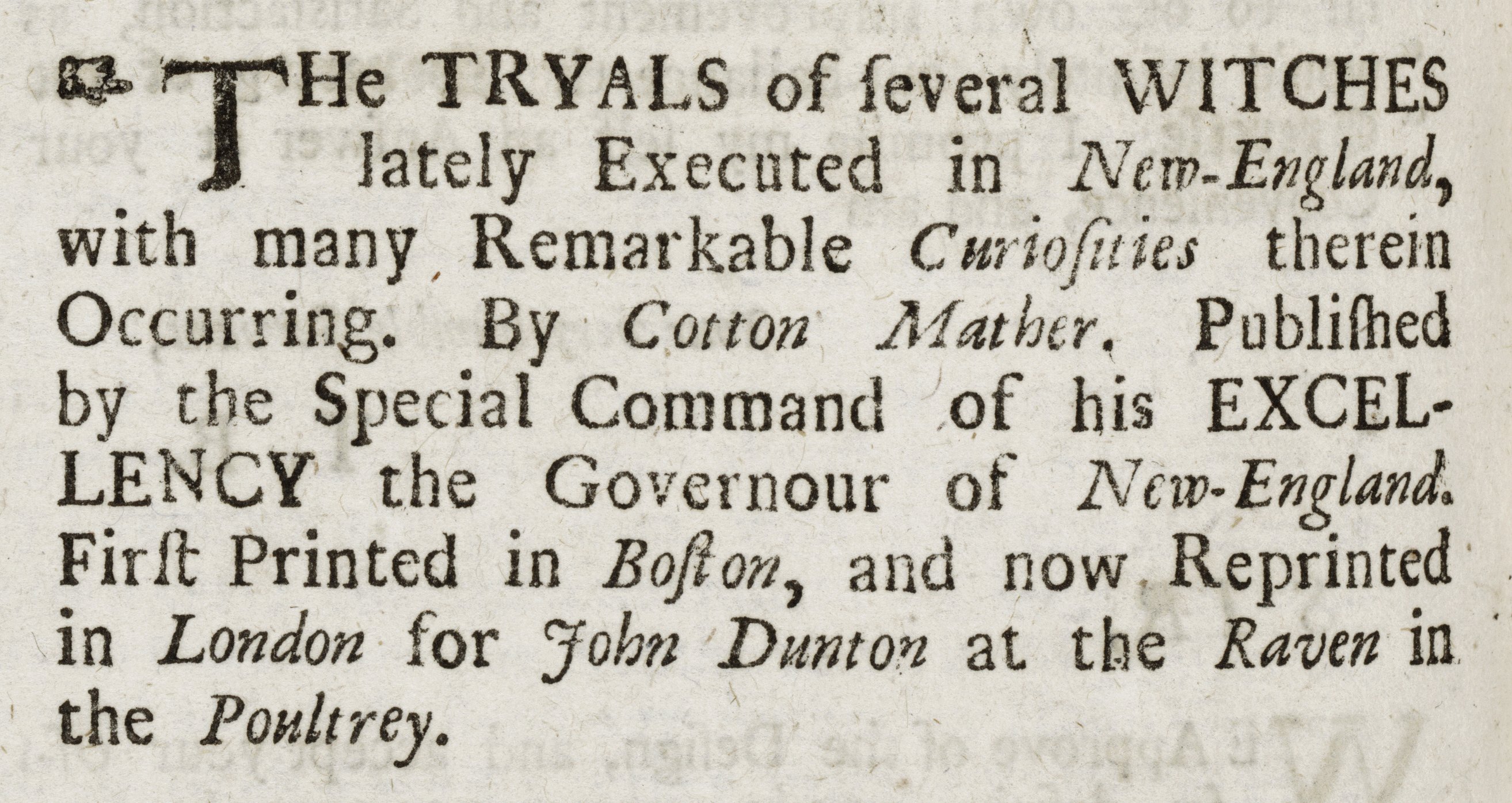

The first American newspaper was printed in 1690. What kinds of remarks were made in the Publick Occurrences – and who made them?

Benjamin Harris was the editor and publisher of Boston’s Publick Occurrences. His first – and last! – issue of the newspaper was printed in 1690 and contained reports that the king of France, Louis XIV, had slept with his daughter-in-law, and also questioned the worth of the colony’s Native American allies. The Massachusetts authorities were quick to shut down such scandalous commentary.

Tell us about the special docent-led tour on October 15. How often will they be run? Is there a size limit?

We regularly offer short tours of the current exhibition prior to Wednesday evening theater performances. These free, docent-led tours showcase highlights of the exhibition. They begin at approximately 6:30 pm in the Great Hall and end by 7:15 pm.

Free tours of the exhibition and building are also offered on weekdays at 11am and 3 pm and on Saturdays at 11am and 1pm. No advance reservations are required, and there is no size limit. However, we do offer special arrangements for group tours – for more information on group tours, please call (202) 675–0395 or email educate@folger.edu.

What would you consider to be the highlight of the collection

This is very difficult. I would probably opt for ‘Mercurius Rusticus,’ because it offers an evocative image of a street seller of seventeenth century newspapers, while at the same time also highlighting how newspapers began to develop the use of imagery as well as text, and formats such as headline news.

Leave us with a cool, little-known fact about the exhibit.

There’s so much fascinating material, it’s hard to choose just one fact! Printing a newspaper involved a lot of physical work – for example, the compositors, the people who set the type, had to work upside down and backwards to lay out the words, letter by letter, as they set up the pages. It might take a compositor an entire day to lay out just one page, so when you think that by 1702 there was a daily newspaper in London, it’s pretty remarkable!

All photos courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

The Folger Shakespeare Library is located at 201 East Capitol Street, SE and is accessible via the Red Line at Union Station or the Blue / Orange line at Capitol South. Thanks to Jason and Amy for a great interview!