Lyndon B. Johnson’s photographer Yoichi Okamoto disappeared behind the President to make this image. Okamoto would have been below the eye line of almost all of the reporters in the room. (LBJ Library/Yoichi Okamoto, p. 118); courtesy National Geographic

Photographs. They’re a common form of expression in media today; they’re everywhere. To many, none are more relevant or as communicative as those taken of the President of the United States. We see them every day in the paper, on websites, on television. “Pictures are worth a thousand words,” says the old adage; none more so true than those of the most powerful and important position in these United States.

But what about the men and women behind those shots? Ever wonder about them – who they are, how they do what they do, what it takes to get “that shot”? John Bredar recently published The President’s Photographer: 50 Years Inside the Oval Office. Bredar primarily chronicles Pete Souza, President Obama’s chief photographer (and former photographer for President Ronald Reagan), through the book while discussing the unique ins and outs of the position with past photographers. We managed – with National Geographic’s help (and a review copy of Brader’s book)- to catch former Presidential photographers Eric Draper and David Hume Kennerly and find out a little bit more about who some of these special and unique individuals are behind the lens.

Access to the President “behind the scenes” by photographers is, in the sense of Presidential history, only a recent development. “Do we really need someone following the President of the United States around every day with a camera?” Bredar asks in his book. When photographer Edward Steichen approached President Lyndon Johnson about it, he posed a simple question: “Just think what it would mean if we had such a photographic record of Lincoln’s presidency?”

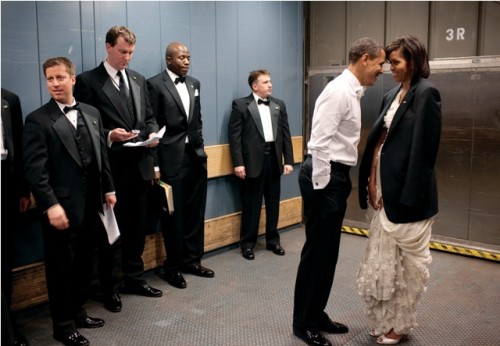

Considered by many to be one of his iconic images— so far—Pete Souza captured a private moment between President Obama and the First Lady on a freight elevator in Washington’s convention center, Inaugural night 2009. (Pete Souza, The White House, p. 6); courtesy National Geographic

Presidential photographs have been taken, both in public and private moments, since the inception of photography. Johnson’s presidency, however, was the first to have such comprehensive coverage of his public and private life during his term, a tradition of sorts that has continued through today. Yoichi Okamato, LBJ’s chief photographer, is held up by many as the “godfather of presidential photography,” setting a high standard that every chronicler since has tried to equal. And just like photography, even getting to be in such a position can be an exercise of “right place, right time.”

Eric Draper came up through the ranks as a news photographer, with a career path that went from community and local news in a small town to national stories and then traveling the world with the Associated Press. After covering the 2000 Presidential campaign, he found himself in the right place at the right time: “When I discovered I had a shot at being [President George W.] Bush’s photographer, all I had to do was ask.”

David Hume Kennerly came up through a similar, but slightly different route to become President Gerald Ford’s photographer. “I started the old fashioned way – I went from a high school photo job, to a small paper, to the Oregonian, to a wire service (UPI), to LIFE magazine and then TIME, to chief White House photographer,” he said. After his stint with Ford, he returned to TIME and then moved on to Newsweek. “Following that path these days is a more difficult one due to the fact that many newspapers have gone out of business, and there are fewer editorial positions available.”

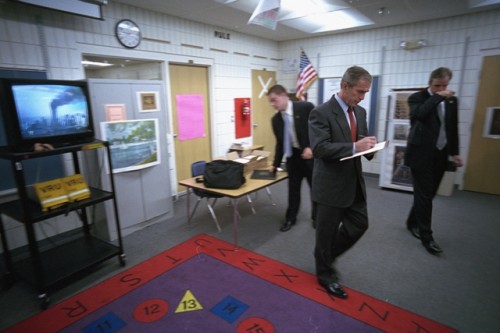

George W. Bush chief photographer Eric Draper’s images from 9/11 tell a riveting story. He described it as one of his hardest days as a photographer. Desperate for information that morning, President Bush takes notes while TV news coverage of the burning towers plays in the background. (Eric Draper/ George W. Bush Presidential Library, p. 172); courtesy National Geographic

The challenges these photographers face can be difficult, though Kennerly thought his position covering politics tends to be easier than other public arenas. “One of the biggest difficulties is just getting people to cooperate with a request to take their photo. In Hollywood, for instance, there are layers upon layers of people whose job it is to ‘protect’ their clients, so getting to actors for a photo shoot has a high degree of difficulty,” he responds. “They also want to own the rights or approve the photos. I don’t like working there. Politicians are easier to deal with generally, and it is one of the reasons I like covering politics.”

Bredar’s book is full of the various challenges many of the photographers have had to face, from long days to surprise schedules to sudden, world-changing events. When Draper interviewed for the job, for instance, Andy Card (Bush’s Chief of Staff) explained that “‘working at the White House is like trying to drink water through a fire hose.'” It’s easy to get exhausted only reading about Pete Souza’s routine just to capture on a daily basis those photos we take for granted every day.

The job can be physically demanding, too, a constant challenge that Draper found during his time in the White House. “It was always challenging to physically keep up with the President Bush, especially during domestic and international motorcades,” he recalled. “He walked fast and greeted people very quickly at events. I was always running and some times jumping out of moving vehicles in order to stay in the bubble.”

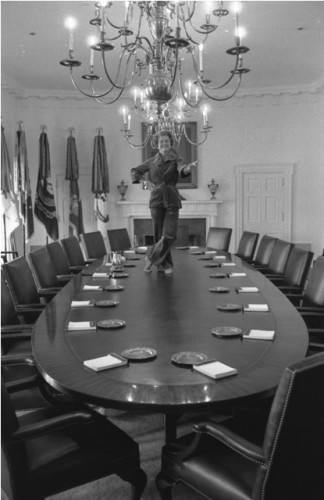

David Hume Kennerly made this picture the day before the Carters moved into the White House. Taking a last tour of the West Wing, Betty Ford told him she’d always wanted to dance on the Cabinet Room table. A former Martha Graham dancer, she slipped off her shoes, hopped on the table and struck a pose. (David Hume Kennerly/Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library p. 133); courtesy National Geographic

Constantly on the go – and on call 24/7 – these men and women behind the camera tend to wear several photographic hats, from portraiture to candid. Adaptability is essential, though each has their own favorite approach. “I’ve never been that good at staging photos and much prefer shooting events or situations as they unfold,” says Kennerly. “I’m always looking for that moment that reveals something about a person’s character in the context of what they are doing.”

Draper agreed. “Some days I would be a portrait photographer. Other days a I would be a documentary photographer. When the President would ride his mountain bike at the ranch I felt like a sports photographer,” he said. “Some situations I had to control like a movie director telling the President and a visiting world leader where to stand and what to do. Once the posed photos were out of the way I could fade into the background and become the fly on the wall and capture real storytelling moments.”

Both Draper and Kennerly told me that objectivity was essential, regardless of what hat they wore. “I’ve always tried to keep my personal opinions out of affecting my photos. It may be ‘Old School,’ but it’s the way I was brought up in the business,” says Kennerly. Their job is that of a chronicler for future history, which requires setting aside personal opinions and focusing on the events within the President’s bubble.

Draper recalled a moment during his time with Bush that summed up his approach, the day the President made the decision to commit troops to Iraq. “I followed the President from the Situation Room where he had just made the decision out to the South Lawn,” he said. “I could see the emotion in his face. His eyes were red from holding back tears. I waited while he walked the entire circle of the South Lawn drive with his two dogs. I made the image of him walking towards me then he spoke to me. ‘Eric, are you interested in history?’ Shaking in my shoes I replied, ‘Yes sir.’ He said, ‘The photos you taking right now are very important.’ Just has he said those words Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Don Rumsfeld walked out to meet the President in front of the Oval Office door.”

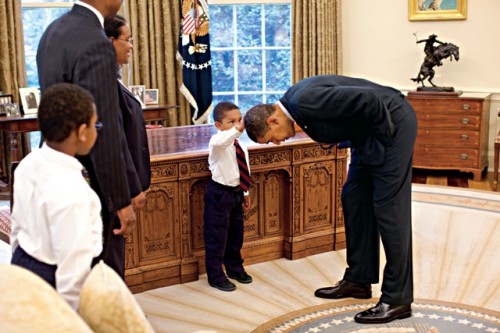

President Obama has said this is one of his favorite photos. White House staffer Carlton Philadelphia brought his family in to meet the President, and at one point, his son declared that he’d been told that he and the President had the same haircut. President Obama bent over so the child could get a better look. (Pete Souza, The White House, p. 24); courtesy National Geographic

“A picture is worth a thousand words, but most Presidents are going to be a lot more candid if the broader public can’t hear those words,” says Bredar in the introduction to his book. The still image is still the most powerful one, he argues, and the camera the least intrusive to record our surroundings. It also allows the photographer to ignore and omit the conversations occurring around them as they record history. Kennerly said “Working discreetly around people is one of the keys [to being successful in this job]. It’s especially important that you not talk about conversations overheard during shooting ‘behind the scenes’ assignments, particularly sharing that information with reporters. A photographer is akin to a lawyer—privileged information needs to stay in the room.”

The President’s photographer is therefore not a journalist nor a reporter. They are ‘silent archivists,’ recording time as it plays out on the Presidential stage – both the personal and the public. Says Souza in the book’s Forward, “I usually tell my friends that, following in the footsteps of those who came before me, I am trying to make timeless photographs that people can look back upon in 50 years. But I recently listened to a long-ago presentation by Okamoto when…he said not 50 years but 500 years. Wow! I thought. Imagine someone combing through my photographs on President Obama in 2510. That really makes me realize that this is visual history I am recording with my camera. I will do my best to take that to heart every day.”

Tomorrow night, National Geographic is holding a private screening their new television special, The President’s Photographer, which will air publicly on Wed, Nov. 24 on PBS (check local listings). The short film, which shadows chief White House photographer Pete Souza, ties into Bredar’s book and will be followed by an open discussion with Bredar and several past White House photographers, including Eric Draper, Robert McNeely, and David Valdez. The event is sold out.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Photographing the President » We Love DC -- Topsy.com

Pingback: Upcoming: Presidential photography forum at the Portland Art Museum – OregonLive.com | The Photo Bargains

It must be amazing to be able to capture and preserve history as it is being lived. Finding the right balance and respect for the subject. The snow pictures of the White House last year were beautiful. These moments shared within a family are amazing.