Chocolate. Most people think they love it. But is it really chocolate they love — or sugar?

That’s a question chocolate maker Steve DeVries might pose. Most chocolate is made industrially and is full of sugar. The normal ratio is two parts sugar to one part cocoa. This sweetness can obscure the delicate and complex flavors of the bean itself.

DeVries found this out firsthand years ago after he bought some cacao beans at a plantation in Mexico. With almost no direction, he brought them home, roasted them until they smelled like brownies, and ground them himself. What DeVries experienced was delicious, “a complexity of flavor I’d never tasted in chocolate before,” he said. “It was like crushing grapes and getting a fine burgundy.” The reason, he discovered, was that chocolate had been overindustrialized.

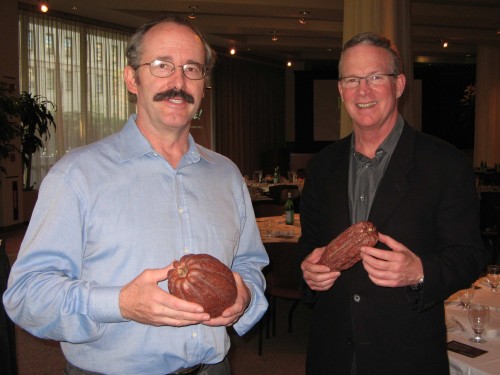

Now head of Denver-based DeVries Chocolate, he is a bean-to-bar chocolate maker. While most makers buy chocolate and form it into bars with various flavorings, he starts from scratch with the beans themselves.

Last night, DeVries explained the process of making chocolate at the National Geographic Live! event Chocolate: From Bean to Bar on April 14. In addition, Biagio Abbatiello of Biagio Fine Chocolate near Dupont Circle led a tasting of artisanal chocolates from around the world. The pair also sat down with me beforehand to answer extra questions, one of which was, “How is DC as a chocolate town?”

First, let’s talk about what happens to chocolate before it arrives in our fair city.

Cacao trees grow 20 degrees north and south of the equator, in places like Mexico, Peru and Brazil. Most beans, about 65%, currently come from Africa, DeVries said. The best come from Brazil.

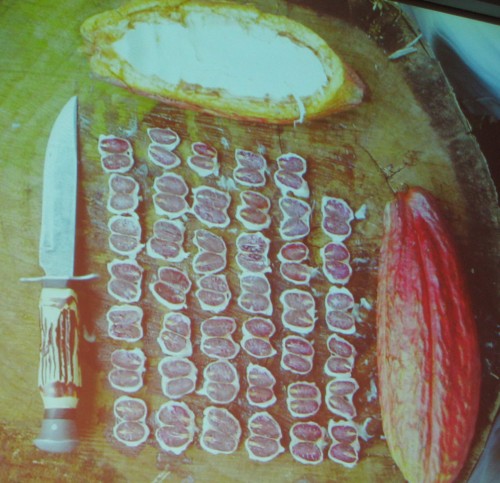

The trees form pods, and inside are the beans. They are seeds covered with a soft, sweet, pear-like mucilaginous pulp, which “doesn’t sound so good,” joked DeVries. The reproduction of cacao is based on that pulp. It needs an animal to take the pod off the tree, open it, take the pulp out and spit the seed onto the ground. Most animals won’t eat the seed because it’s bitter, said DeVries. That’s the part we make into chocolate.

The seeds are fermented, spread out to dry, then roasted. If you crack one open, which we did, you’ll see a dark, crumbly, nut-like center where the leaves would have formed. These centers, called nibs, are then ground. No water is needed — warm them a little, and the 56% cocoa butter they contain melts and “becomes like a frosting,” said DeVries.

Next comes conching, invented by Rudolph Lindt in 1879. Lindt’s machine pressed the nibs between a roller and a granite base for three and one-half days, smoothing them and changing the flavor of their acids. Conching and tempering produce a basic chocolate that can be patted down and pushed into forms.

Things like the quality of the beans used, the degree of roasting, and the ingredients such as sugar and milk added along the way can greatly affect the taste of the final product. In fact, it’s easy to forget chocolate comes from a plant.

“We’ve sold chocolate as an industrial product more so than an agricultural one, and everyone expects it to be the same from year to year,” said DeVries. Nobody expects the same from wine or cheese. With them, as with good chocolate, some are challenging the first time you try them, he said. “Sometimes I get killed on tastings” when introducing an unusual chocolate, DeVries said. “It’s not what people expect to have, so they don’t like it.”

Industrial chocolate producers deal in large volumes and can’t afford to have chocolate people don’t like, DeVries said. So they make chocolate to the lowest common denominator. And they add lots of sugar to keep the taste consistent. That way, if you like chocolate once, you always will.

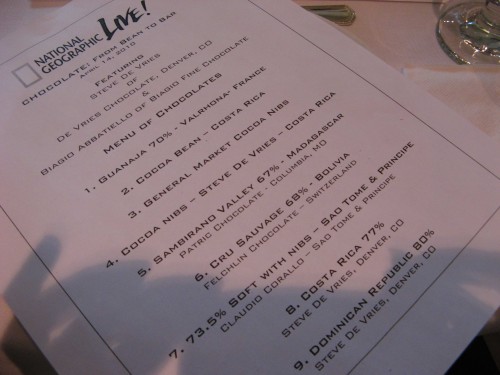

Small chocolate makers, however, can follow their view of what chocolate can be. And that is where shops like Biagio enter the picture. Abbatiello brought in several chocolates to try, all far removed from the drugstore variety. The Sambirano Valley 67% from Madagascar, made by Patric Chocolate in Missouri, brought up adjectives like “fruity” and “smooth.”

The Cru Savage 68%, made by Switzerland’s Felchlin Chocolate, is very popular at Biagio. It came from trees planted by priests in Bolivia 250 years ago, said Abbatiello, and was described as “woody,” “spicy,” “nutty,” and “with a long finish.”

Being somewhat new to this, I agreed but didn’t have too much to add on my own until we got to the next kind, the 73.5% Soft with Nibs from Sao Tome & Principe, by Claudio Corallo. This one was not conched, so it had the crunch of nibs. But it also had a bite that tasted like booze. Some at my table agreed. Others called it “hummus-y” and “earthy” and “like dirt,” and one lady suggested drinking it with Pu-erh tea, an aged, fermented tea. It was good, but definitely unusual. “Most people love it or hate it,” said Abbatiello. Isn’t that half the fun of it?

After the bean, two kinds of nibs, and six kinds of chocolate came a surprise. Not yet available for purchase, this chocolate earned the widest range of descriptors of all. It seemed sweeter than the others, reminiscent of oranges, olives, Sweet Tarts, flowers, and the astronaut’s favorite drink, Tang.

But is DC ready for chocolate that tastes like dirt?

Abbatiello says yes. A self-described “chocophile from birth” who discovered single-origin chocolates while living near a chocolate shop in Paris in the mid-80s, he is a flight attendant who’s traveled the world. He opened his store at 1904 18th St. NW in late 2006 so that he could find good chocolate at home, and it’s going quite well.

“The reception in DC has been amazing,” he said. “Except for the customer who walked in on the shop’s opening day, picked up a piece of French chocolate and exclaimed, ‘Eight dollars for a bar of chocolate? This place is going to fold quickly.’”

Luckily, she was wrong. DC has the demographics to support such a shop, with a lot of well-educated residents who understand that they are paying for quality, said Abbatiello.

What happens when someone tries a chocolate made with good beans for the first time? “I’ve seen people rise out of their seats,” Abbatiello said. “The transformation has been amazing. People come in the shop and say, ‘We hate you. We can’t eat other chocolate any more!’”

These are the folks whose love for chocolate is true.

Many thanks to National Geographic Live! for allowing me to attend with a complimentary ticket. Keep an eye out for the May events list — and the chance to win free tickets here on We Love DC!