‘Oxcart Belly’

courtesy of ‘MrGuilt’

In the late 1950s, during the heyday of aviation and the dawning of space flight, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) approached Lockheed to develop a new aircraft that could overfly the Soviet Union. The CIA’s current plane (at the time) was the U-2, which served admirably in its role as a high-flying reconnaissance plane but was still susceptible to being shot down by high-altitude Surface-to-Air Missiles (SAM). Such an incident did occur in 1960, when Gary Powers was shot down while conducting an overflight over the U.S.S.R.

The result was the A-12, code name OXCART, which ended up in a different role as the Vietnam war broke out. The CIA’s spy plane flew several black missions during the war before being phased out and replaced by the U.S. Air Force’s SR-71 Blackbird. On Thursday evening at the International Spy Museum, many aspects of the A-12 Oxcart program will be discussed by several experts, including CIA chief historian David Robarge, J-58 engine inventor Robert B. Abernethy, flight specialist Thornton D. Barnes, CIA officer S. Eugene Poteat, and pilot Kenneth Collins.

For a taste of the discussion, we managed to pin down CIA chief historian David Robarge for a few minutes to discuss the Oxcart and BLACK SHIELD programs.

‘USS Intrepid (CV-11)’

courtesy of ‘Obskurantist’

In 1957, the CIA approached Lockheed’s famed “Skunk Works,” the aircraft manufacturer’s Advanced Development Projects section, to design a new high-altitude aircraft capable of flying at Mach 3 or greater and would have a low radar cross section, making it virtually undetectable by Soviet radar. Both Lockheed and Convair ended up making proposals for the CIA’s new aircraft. Convair’s design, “Kingfish,” had a smaller radar cross section but Lockheed’s A-12 design would cost less. “The decisive factor was the companies’ respective records on production projects,” says Robarge. “Convair’s work on the B-58 Hustler had been plagued with delays and cost overruns, whereas Lockheed had produced the U-2 on time and under budget. Moreover, Lockheed had experience working on a ‘black’ project, but Convair did not.”

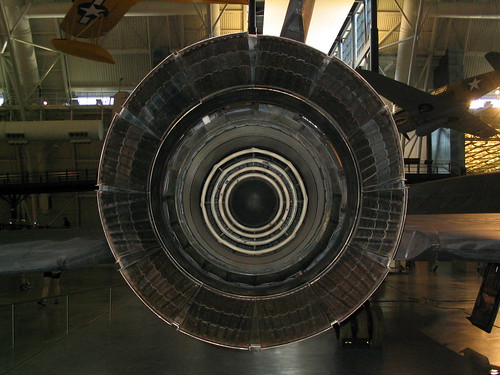

Once approved and the first prototypes produced, the A-12 program was transferred to the secret Groom Lake facility (also known as “Area 51” by conspiracy theorists) for testing. The first five A-12s used Pratt & Whitney J75 engines, enabling the plane to achieve Mach 2. “The A-12 could not have performed its mission because it could not have flown high enough and fast enough to elude enemy surface-to-air missiles,” says Robarge. A more powerful engine was necessary; enter the J58. Developed initially for the U.S. Navy, Lockheed selected the engine design in part because the J58 – a hybrid turbojet/ramjet engine – could operate on afterburner for extended periods of time. “Just one J58 could produce as much power (160,000 horsepower) as all four of the huge turbines on an ocean liner of the day,” said Robarge.

During the A-12’s testing phase, U.S. policy shifted away from overflying the Soviet Union, deeming it too dangerous and largely unnecessary with the advent of satellites. Operation BLACK SHIELD was devised as the military conflict in Vietnam was escalating and other collection platforms could not provide the intelligence needed in a timely or secure fashion,” says Robarge. “Satellites did not have a quick reaction capability and so were irrelevant for tactical wartime operations, and several U-2 and drones had been lost over Communist China and would have been equally vulnerable over North Vietnam.” Even as the A-12 program was canceled in late 1966, BLACK SHIELD began in 1967 using the few A-12s declared operational by Lockheed. And by all accounts, the CIA considered the operation – which lasted only 26 missions – a success.

‘J-58 Engine’

courtesy of ‘Roger Smith’

“The photography collected by the A-12 and interpreted by analysts provided valuable intelligence on enemy missile defenses, troop movements, and military facilities; assessed bomb damage and aided in targeting activities; and dispelled concern that North Vietnam was planning to use surface-to-surface missiles against the South,” replied Robarge. “Not a major contribution overall, but highly useful under the circumstances, and no doubt some U.S. pilots are alive today because of what the A-12 collected about enemy SAM sites.”

The “new” A-12 program hit the public spotlight shortly after the end of BLACK SHIELD. The Defense Department grew concerned it could not adequately explain why the USAF was spending so much money on two versions of the A-12 platform: the YF-12A, a hypersonic fighter, and the SR-71 Blackbird, the USAF’s reconnaissance version. As such, President Johnson made the decision to “out” the SR-71 Blackbird program to focus public attention on it, allowing the CIA’s component to remain a secret.

The overall differences between the public SR-71 and the A-12 is minimal to a general observer, as both planes retain the same basic exotic shape. The differences, observed Robarge, are more in their performance aspects. “The SR-71 was designed to fly longer missions than the A-12 and so is about six feet longer to accommodate the additional fuel,” he said. “Because it also is about 15,000 pounds heavier when fully loaded, It has more prominent nose and body chines to provide lift. The A-12 carried a pilot who also operated the camera system, the only sensor it carried; the SR-71 carries a pilot and a reconnaissance systems officer who operated the additional radar system and ELINT [electronic intelligence] sensor.” However, both aircraft could reach 90,000 feet and above at Mach 3.3 and higher.

‘SR-71A #61-7971’

courtesy of ‘Roger Smith’

The A-12 Oxcart program sparked a number of design innovations in general aviation history, including achieving speeds greater than Mach 3, the hybrid turbojet/ramjet, using a full titanium structure, and high-altitude stealth flight. Less known are the innovations by the A-12 program for the CIA. “The A-12’s legacy endured in the SR-71 program, which flew over 3,500 operational sorties to many trouble spots around the world during the subsequent 21 years,” said Robarge. More importantly, “OXCART, combined with the U-2 and satellite programs, also helped establish the CIA as the nation’s preeminent organization in research and development, collection, and analysis of imagery intelligence until the 1990s, when that responsibility went to the military.”

Even today, 44 years after its official retirement (and 12 years after the SR-71’s second retirement), the A-12 and its design siblings still invoke a sense of exotic wonder. Partially from its secret origins and mysterious operational history, and partially from design elements that make it so unlike other conventional aircraft, the A-12 is firmly ensconced in America’s aviation history. Plus, it’s just plain cool to look at.

Join CIA chief historian David Robarge and a panel of experts at the International Spy Museum on Thursday, Sept 23 at 6:30 p.m. Tickets may be purchased online through the Museum’s website, in person at the box office, or by phone.

For more information on the A-12 Oxcart program, the CIA has released nearly 3,500 documents regarding the program under the Freedom of Information Act. Many thanks to the CIA for lending me David Robarge for his invaluable assistance with this feature.

The statement that both the A-12 and the SR-71 had the same performance numbers cannot be accurate. The SR-71, with one extra person, six feet longer, more sensors, overall 7 and a half tons heavier than the A-12, simply could not fly as fast or as high as the A-12.

This is a really interesting piece. Thought you might also be interested in reading this profile that I did today of one of the intelligence analysts who spent his career as a deep cover spy in the 50’s, looking at the photos taken by U-2s to try and figure out where the Soviets were housing their satellites and missiles. You can read about Tony at http://peoplesdistrict.com/tony-on-a-career-in-espionage

Pingback: Tweets that mention OXCART: CIA Innovation and a Cool Spy Plane » We Love DC -- Topsy.com